What’s the diagnosis?

An asymptomatic annular plaque on the forehead

Case presentation

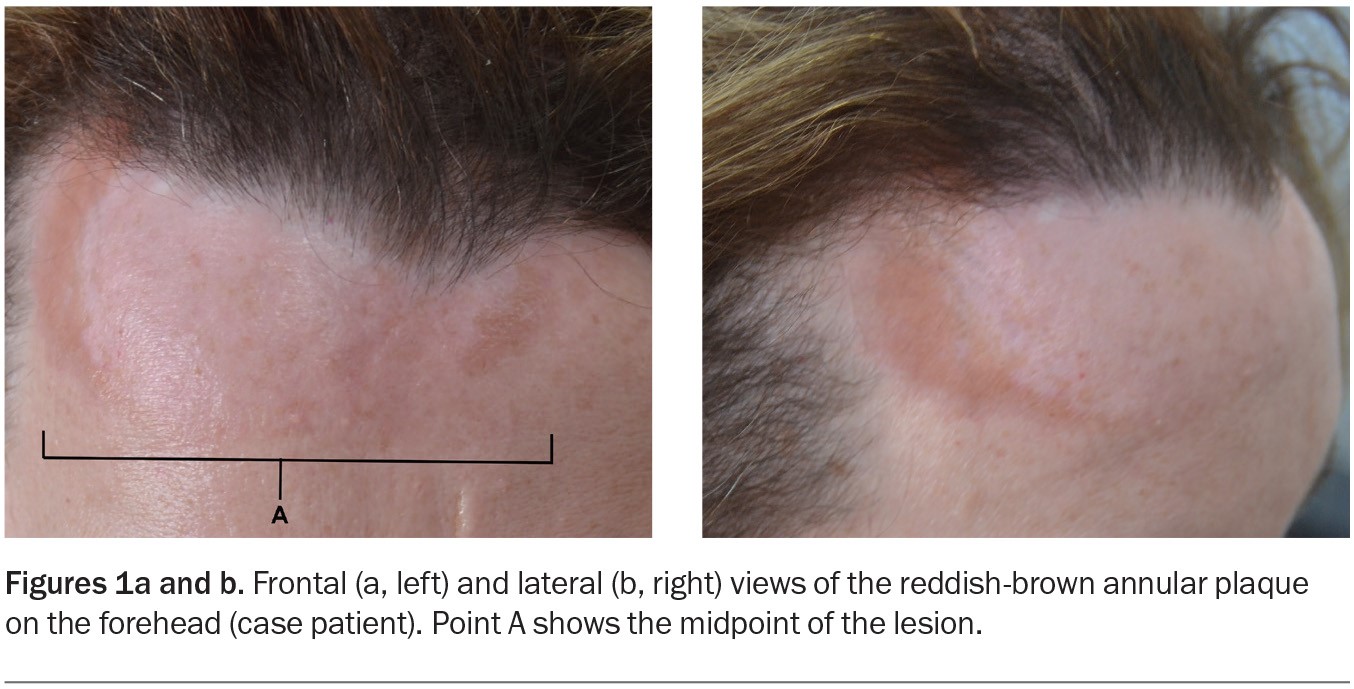

A 50-year-old woman presents with a three-year history of a reddish-brown plaque on her forehead (Figures 1a and b). The plaque, which is 10 cm in diameter and gradually enlarging, is annular, indurated and smooth without scale. It is not causing symptoms and sensation to the area is normal.

The patient has no significant past history other than plaque psoriasis, which has been in remission for 25 years. She does not have any systemic or gastrointestinal symptoms.

A punch biopsy is performed and histological examination of the specimen demonstrates dermal non-necrotising granulomatous inflammation.

Differential diagnoses

Conditions to consider among the differential diagnoses include the following.

Tinea faciei

Tinea faciei is a superficial dermatophyte infection of the glabrous (hairless) skin of the face.1 It typically presents as a solitary circular lesion that is red and scaly with a raised leading edge. The condition may be asymptomatic but can be itchy or painful. Clinically, it closely resembles tinea corporis (ringworm), which is seen more often but does not occur on the face.2 Trichophyton rubrum is the most common causative agent; however, zoophilic fungi such as Microsporum canis (from household pets) and Trichophyton verrucosum (from farm cattle) may also be responsible.2 A diagnosis of tinea faciei is based on clinical presentation and confirmed by culture of skin scrapings.

For the case patient, the reddish-brown colour of the lesion and its absence of scale, as well as the histopathological findings, do not suggest a diagnosis of tinea faciei.

Discoid lupus erythematosus

Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) is the most common type of chronic cutaneous erythematosus and can occur in localised or generalised form.3 Rarely, it can be associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) – about 5% of patients with localised DLE and 15% with generalised DLE develop SLE.4 The incidence of DLE is higher in people with skin of colour.5 Disease onset typically occurs in middle age, with women more frequently affected than men.6

DLE characteristically presents with red, scaly papules and plaques that are raised and inflamed and have a photodistribution on the face (cheeks, nose, forehead) and scalp.5 Lesions in hair-bearing areas of the scalp may show a characteristic plugging of keratin within the hair follicles (follicular hyperkeratosis). Symptoms may include itching, burning and sensitivity to sunlight. The lesions may cause atrophic scarring, skin pigmentation changes and alopecia.

DLE is usually diagnosed by biopsy, which typically reveals an interface dermatitis involving hair follicles and a perivascular and periappendageal lymphocytic infiltrate in the upper and lower dermis.6 If the results of routine histopathology are equivocal then direct immunofluorescence (DIF) testing of lesional skin can be useful (note that biopsy specimens for DIF should be placed in saline-soaked gauze as opposed to formalin solution).7,8

For the case patient, the location of her lesion (forehead) made DLE a differential diagnosis. However, the histological finding of non-necrotising granulomatous inflammation is not consistent with this condition.

Erythema annulare centrifugum

A rare condition, erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) is a benign, chronic skin disorder characterised by annular or circular, erythematous plaques with a trailing scale that expand centrifugally.9 The lesions are most frequently seen on the thighs, buttocks and upper arms.10 EAC can occur at any age but is most common in middle-aged adults, with males and females affected in equal number.11

EAC is thought to be a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction that involves the interplay of various inflammatory mediators and is associated with infections, medications and autoimmune disorders.12,13 A known mimic of many skin conditions, its diagnosis requires a combination of clinical evaluation and skin biopsy; other diagnostic tests might also be indicated to exclude possible underlying conditions.9

EAC is not the correct diagnosis of the case patient. Clues include the absence of a trailing scale for the lesion and the presence of non-necrotising granulomatous inflammation seen on histological examination.

Granuloma annulare

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a benign, self-limiting, inflammatory skin condition that presents as an annular eruption. Both localised and generalised variants occur. Lesions are typically between 2 and 5 cm in diameter and found on the hands and feet. GA is most frequently seen in children and young adults but may occur at any age; it is more common in females than in males.14,15 Most patients are asymptomatic.

The exact aetiology of GA is unknown but it may be associated with certain diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, thyroid disorders and HIV infection. Diagnosis is based on clinical features and skin biopsy, with histopathological examination demonstrating focal collagen degeneration, inflammation with interstitial histiocytes and mucin deposition.16

GA is not the correct diagnosis for the case patient. The facial location of the lesion made this diagnosis less likely. In addition, the histopathological findings were not consistent with GA – visualising dermal mucin, in particular, can favour a diagnosis of GA but was absent in this case.14

Lupus vulgaris

Lupus vulgaris, a rare, chronic form of cutaneous tuberculosis, is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Lesions are most commonly found on the face, neck and extremities and typically start as soft, solitary plaques that are brown-red in colour with centrifugal growth.17 At presentation, they are typically brown-red, nodular or plaque-like skin lesions with well-defined borders. The lesions – which may be present for several years before diagnosis – are usually painless but may become ulcerated or crusted.

Histological examination will typically show caseating epithelioid granulomas that contain acid-fast bacilli. Other investigations that may be appropriate include tuberculin skin test (Mantoux test), serum Quantiferon-gold test, sputum culture and chest x-ray.18

Australia has a low incidence of tuberculosis. Risk factors include being born overseas, exposure to a person with tuberculosis, diabetes mellitus and homelessness.19 Patients with tuberculosis are usually managed through a dedicated infectious diseases unit. Cutaneous tuberculosis is a notifiable condition. Contact tracing should be discussed, given the risks of infection to close contacts.20

For the case patient, a number of factors prompted consideration of this diagnosis, particularly the colour and smooth, nonscaly appearance of the lesion and its slow pattern of growth. However, several factors in the clinical presentation made this diagnosis unlikely, including a lack of risk factors and no travel or exposure history suggestive of tuberculosis (or leprosy). Most significantly, her biopsy result showed noncaseating granulomas as opposed to caseating granulomas that are typically found in tuberculosis. In addition, Quantiferon-TB gold testing was performed and returned a negative result.

Cutaneous sarcoidosis

This is the correct diagnosis. Sarcoidosis is a multisystem inflammatory disease characterised by noncaseating granulomas that most frequently affect the lungs, eyes, skin, liver and lymphatic system.21 It has a slight female predominance and is typically diagnosed in middle age.22 There is a higher incidence in Scandinavians and people with skin of colour.22 Cutaneous involvement occurs in up to 35% of cases with systemic sarcoidosis and may be the first presentation of systemic disease.21,23 The face is the most common site for cutaneous lesions.23

Cutaneous sarcoidosis has been described as a dermatological masquerader, given its vast array of clinical presentations.23 Lesions may be specific or nonspecific. Specific lesions, which demonstrate the classic noncaseating granulomas on histopathology, include:22,23

- lupus pernio – nodules or plaque-like lesions that typically affect the midface, particularly the alar rim, but may also be found on the ears, fingers and toes

- sarcoid plaques and papules – lesions that present in multiple colours, including skin-coloured, reddish-brown (as in this case) or even violaceous

- subcutaneous nodules – these are typically firm and raised, with a range in size (up to several centimetres in diameter) and often reddish or purplish colour, and can be seen or felt just beneath the surface of the skin; they can occur anywhere on the body but are commonly found on the face, arms and legs

- thickening of old scars (scar sarcoidosis).

Nonspecific lesions (often seen in patients with sarcoidosis but lacking the classic histological features) include erythema nodosum, nummular eczema, erythema multiforme, calcinosis cutis and pruritis.23

Patients with sarcoidosis may report constitutional symptoms, such as weight loss, fatigue, fevers, chills, night sweats and loss of appetite.21 Other symptoms may occur, depending on the organs affected: for example, headaches, ataxia and visual disturbances may occur in neurosarcoidosis; palpitations or syncope may occur in cardiac sarcoidosis.24,25

Diagnosis

Cutaneous sarcoidosis is generally diagnosed through skin biopsy and histopathological examination. Chest imaging may be performed and lung biopsy specimens taken to determine lung involvement. The selection of additional investigations is tailored to identification of potential organ-specific disease. Measurement of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels can be useful for assessing disease activity, but the test has low sensitivity and specificity.26

Management

The choice of therapy for cutaneous sarcoidosis should be tailored to disease severity and the preferences of the patient, noting that often spontaneous resolution may occur.21 First-line therapy involves very potent topical corticosteroids (e.g. clobetasol propionate 0.05%) or injected corticosteroids (e.g. triamcinolone acetonide 10mg/1mL injection) to treat inflammation and granuloma formation. Caution is required when using corticosteroids that are injected dermally because local side effects may include skin atrophy and pigmentation changes.27 Systemic agents are reserved for patients with severe cutaneous disease or coexistent systemic pathology, with oral prednisolone the primary agent.28 Corticosteroid-sparing immune modifying agents may be trialled, such as methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil or hydroxychloroquine.28 There is emerging evidence that Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors may play a role in inducing remission in patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis.29

Outcome

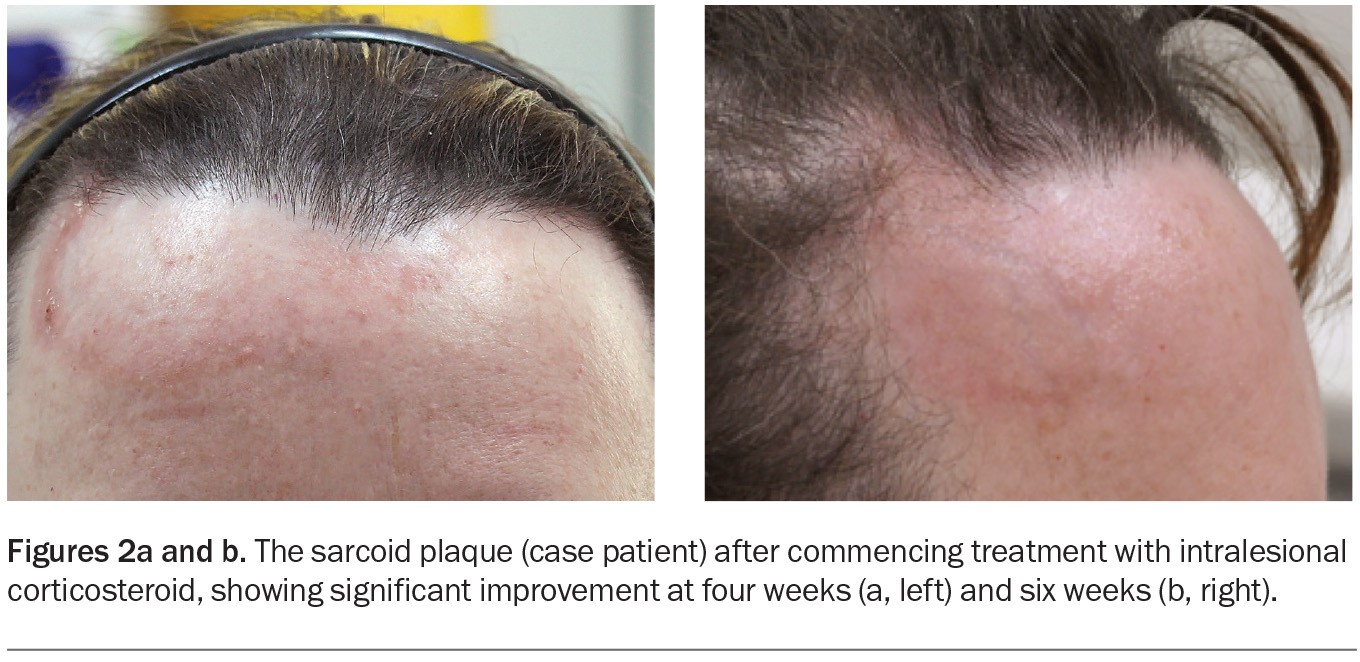

The case patient was diagnosed with cutaneous sarcoidosis. The plaque on her forehead was treated with intralesional triamcinolone acetonide, and significant improvement was observed after four and six weeks (Figures 2a and b). Two further injections were performed at six-week intervals, and near-complete resolution was achieved.

Subsequently, the patient underwent thoracic CT scanning, which confirmed classic hilar lymphadenopathy. She was referred to a respiratory physician for lung function testing and review. No other organ involvement was identified.

Learning points

- Cutaneous sarcoidosis has a vast array of possible clinical presentations. Lesions may be specific (containing noncaseating granulomas) or nonspecific.

- Cutaneous sarcoidosis is often the first presentation of systemic disease.

- First-line therapy for cutaneous sarcoidosis involves topical or intralesional corticosteroids. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Lin RL, Szepietowski JC, Schwartz RA. Tinea faciei, an often deceptive facial eruption. Int J Dermatol 2004; 43: 437-440.

2. Tinea faciei. DermNet NZ; 2003. Available online at: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/tinea-faciei (accessed January 2024).

3. McDaniel B, Sukumaran S, Koritala T, Tanner LS. Discoid lupus erythematosus. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing [internet]; 2023.

4. Callen JP. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a personal approach to management. Australas J Dermatol 2006; 47: 13-27.

5. Joseph AK, Windsor B, Hynan LS, Chong BF. Discoid lupus erythematosus skin lesion distribution and characteristics in Black patients: a retrospective cohort study. Lupus Sci Med 2021; 8: e000514.

6. Crowson AN, Magro C. The cutaneous pathology of lupus erythematosus: a review. J Cutan Pathol 2001; 28: 1-23.

7. Oakley A. Discoid lupus erythematosus. DermNet NZ; 2015 [updated 2022]. Available online at: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/discoid-lupus-erythematosus (accessed January 2024).

8. Zhang G. Direct immunofluorescence: DermNet NZ; 2017. Available online at: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/direct-immunofluorescence (accessed January 2024).

9. McDaniel B, Cook C. Erythema annulare centrifugum. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing [internet]; 2023.

10. Koch K. Erythema annulare centrifugum: DermNet NZ; 2019. Available online at: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/erythema-annulare-centrifugum (accessed January 2024).

11. Boehner A, Neuhauser R, Zink A, Ring J. Figurate erythemas – update and diagnostic approach. JDDG: J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2021; 19: 963-972.

12. Kim KJ, Chang SE, Choi JH, Sung KJ, Moon KC, Koh JK. Clinicopathologic analysis of 66 cases of erythema annulare centrifugum. J Dermatol 2002; 29: 61-67.

13. Chuang FC, Lin SH, Wu WM. Erythromycin as a safe and effective treatment option for erythema annulare centrifugum. Indian J Dermatol 2015; 60: 519.

14. Chatterjee D, Kaur M, Punia RPS, Bhalla M, Handa U. Evaluating the unusual histological aspects of granuloma annulare: a study of 30 cases. Indian Dermatol Online J 2018; 9: 409-413.

15. Cyr PR. Diagnosis and management of granuloma annulare. Am Fam Physician 2006; 74: 1729-1734.

16. Schmieder SJ, Harper CD, Schmieder GJ. Granuloma annulare. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing [internet]; 2023.

17. Barbagallo J, Tager P, Ingleton R, Hirsch RJ, Weinberg JM. Cutaneous tuberculosis: diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol 2002; 3: 319-328.

18. Ngan C. Cutaneous tuberculosis. DermNet NZ; 2003 [updated 2015]. Available online at: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/cutaneous-tuberculosis (accessed January 2024).

19. Coorey NJ, Kensitt L, Davies J, et al. Risk factors for TB in Australia and their association with delayed treatment completion. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2022; 26: 399-405.

20. Communicable Diseases Network Australia. Tuberculosis – CDNA National Guidelines for Public Health Units Australia [v. 3.0]. Australian Government Department of Health; 2022. Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/tuberculosis-cdna-national-guidelines-for-public-health-units (accessed January 2024).

21. Yanardag H, Tetikkurt C, Bilir M, Demirci S, Iscimen A. Diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis; clinical and the prognostic significance of skin lesions. Multidiscip Respir Med 2013; 8: 26.

22. Ungprasert P, Ryu JH, Matteson EL. Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of sarcoidosis. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes 2019; 3: 358-375.

23. Katta R. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: a dermatologic masquerader. Am Fam Physician 2002; 65: 1581-1584.

24. Hussain K, Shetty M. Cardiac sarcoidosis. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing [internet]; 2023.

25. Lacomis D. Neurosarcoidosis. Curr Neuropharmacol 2011; 9: 429-436.

26. d’Alessandro M, Bergantini L, Perrone A, et al. Serial investigation of angiotensin-converting enzyme in sarcoidosis patients treated with angiotensin-converting enzyme Inhibitor. Eur J Intern Med 2020; 78: 58-62.

27. Firooz A, Tehranchi-Nia Z, Ahmed AR. Benefits and risks of intralesional corticosteroid injection in the treatment of dermatological diseases. Clin Exp Dermatol 1995; 20: 363-370.

28. Paolino A, Galloway J, Birring S, et al. Clinical phenotypes and therapeutic responses in cutaneous-predominant sarcoidosis: 6-year experience in a tertiary referral service. Clin Exp Dermatol 2021; 46: 1038-1045.

29. Damsky W, Thakral D, Emeagwali N, Galan A, King B. Tofacitinib treatment and molecular analysis of cutaneous sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med 2018; 379: 2540-2546.

Skin lesions